Bitcoin Mining - The Definitive Guide

You can make money from mining, but the better question is whether it’s profitable or not. Our guide outlines what you need to know about Bitcoin mining.

Updated 8 August 2023

Understand the Basics: Mining is a process used in decentralised digital asset networks where individuals or consortiums dedicate computing resources to process cryptocurrency transactions. Bitcoin mining is an abstract concept casually worked into articles and discussions in a way that implies everyone is familiar with this deeply complex process. If you’re exhausted from hearing about Bitcoin and cryptocurrency mining without knowing anything, this guide will outline what you need to know.

Important: Most cryptocurrencies rely on mining as a means to crowdsource transaction processing resources in a decentralised environment. The fundamental concept of mining is consistent across many cryptocurrencies, but other networks implement different schemes and algorithms. This guide will lean towards the Bitcoin mining ecosystem unless it’s explicitly mentioned anywhere, so assume we’re talking about Bitcoin and not another crypto asset. Naturally, cryptocurrency mining is highly technical, so consider this guide as a surface level introduction.

Summary

Our guide outlines:

Know This First - Can I Make Money from Bitcoin Mining?

Understand the Basics: Mining is a process used in decentralised digital asset networks where individuals or consortiums dedicate computing resources to process cryptocurrency transactions. Bitcoin mining is an abstract concept casually worked into articles and discussions in a way that implies everyone is familiar with this deeply complex process. If you’re exhausted from hearing about Bitcoin and cryptocurrency mining without knowing anything, this guide will outline what you need to know.

Important: Most cryptocurrencies rely on mining as a means to crowdsource transaction processing resources in a decentralised environment. The fundamental concept of mining is consistent across many cryptocurrencies, but other networks implement different schemes and algorithms. This guide will lean towards the Bitcoin mining ecosystem unless it’s explicitly mentioned anywhere, so assume we’re talking about Bitcoin and not another crypto asset. Naturally, cryptocurrency mining is highly technical, so consider this guide as a surface level introduction.

Summary

- Mining is the procedure for processing and validating blocks of Bitcoin transactions. Miners are the linchpin of the Bitcoin network, and without them, the Bitcoin network would come to a standstill.

- Because cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin depend on advanced encryption algorithms, processing transactions requires powerful computational resources.

- Confusingly, the mining difficulty doesn’t have much to do with the number of transactions or network congestion. The size of a Bitcoin block is capped at 1MB, and the size of a basic Bitcoin transaction is approximately 226 bytes, meaning each block can fit at least 4,400 transactions.

- Ironically, the network artificially increases complexity to maintain a target interval of one block every ten minutes. The more resources allocated to the network, the more complexity increases to prevent blocks from being mined too quickly.

- Miners are incentivised by transaction fees pledged by payers and newly minted coins created whenever a block is mined. The current rate is 6.25 BTC per block and reduces approximately every four years.

- Miners compete against each other to be the first to process a block, which entitles them to earn the reward and the cumulative amount of transaction fees.

Our guide outlines:

- The economics of Bitcoin mining

- The Bitcoin mining process explained

- The puzzle Bitcoin miners solve

- Frequently Asked Questions

Know This First - Can I Make Money from Bitcoin Mining?

- In a nutshell, you can make money from mining, but the better question is whether it’s profitable or not. Without joining a mining pool and purchasing special mining equipment, it's unlikely to be profitable given the cost of electricity that's incurred.

- New Zealand's relatively high power prices, which are the biggest contributor to costs, mean that overseas cost estimate data may not be relevant for local miners. While there are always exceptions, we don't believe bitcoin mining to be a profitable venture for typical individuals.

The economics of Bitcoin mining

Before explaining what mining is, it’s essential to understand why anyone would want to do it first; the answer is for financial compensation. Bitcoin miners are incentivised in two ways; through block rewards and transactions fees.

Block rewards

- Miners are primarily incentivised by a block reward which consists of newly created, or minted, Bitcoins.

- The first miner to complete to block automatically receives the new Bitcoins. Currently, the block reward stands at 6.25 BTC.

- When the Bitcoin network launched in 2009, the block reward was set at 50 BTC per block. The reward is halved every 210,000 blocks, and so far, the reward has been halved three times.

- The next Bitcoin halving event is expected to take place in min-March 2024 once block 839,999 is mined, at which point, the block reward will be decreased to 3.125 BTC per block.

- Since the number of Bitcoins that can be mined is capped at 21 million, best estimates predict all the Bitcoin will be mined by the year 2140.

Transaction fees

- Bitcoin transaction fees are voluntary. Payers set the fee they’re willing to pay when initiating a transaction. The first miner to complete a block earns the sum of fees alongside their block reward.

- Taking at random, block 681479, mined on the 2nd of May at 18:30, contained 1,787 transactions and accumulated 0.90047553 BTC (NZ$70,900) in fees. In a single day, miners can earn more than 100 BTC in fees and in April, they earned on average 145.9 BTC per day.

- When sending a Bitcoin transaction from a wallet, you can set the fee you’re willing to pay the miner. Fees are expressed as Satoshi per byte (sat/B). A Satoshi is 0.00000001 BTC; it’s one hundred millionths of a Bitcoin and is the lowest denomination possible.

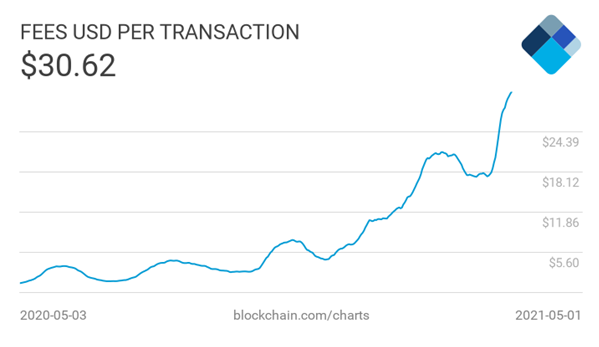

- Transaction fees can be volatile and, generally, increase in tandem with the price of BTC and the associated growth of participants. The average fee paid per transaction for the past 30-days is NZ$42.42. This time last year, the average cost of a Bitcoin transaction was NZ$1.12.

Source: Blockchain.info

Although forty dollars sounds relatively high, it’s worth noting that a single transaction can consist of a batch of payments. For example, in April 2021, there was an average of 279,777 transactions per day; meanwhile, there were 742,317 payments per day. Based on those assumptions, we can presume the actual cost per payment is more like NZ$16.

Miners can prioritise which transactions to process first and prefer transactions yielding higher fees. Presently, there are 24,200 unconfirmed BTC transactions, and that number has crept above 100-thousand on occasion. The overwhelming majority of transactions stuck in the memory pool are paying network fees of seven sat/B or less.

Miners can prioritise which transactions to process first and prefer transactions yielding higher fees. Presently, there are 24,200 unconfirmed BTC transactions, and that number has crept above 100-thousand on occasion. The overwhelming majority of transactions stuck in the memory pool are paying network fees of seven sat/B or less.

The Bitcoin mining process explained

Mining is a function of the Bitcoin network, and it’s one of the final steps before a transaction is settled.

Firstly, you initiate a transaction from your wallet. A transaction must be authorised by a signature generated by a matching public and private key combination. Transactions with valid signatures are broadcast to a Bitcoin node.

A Bitcoin node does two things; it hosts a memory pool (mempool) of unconfirmed transactions, which is approximately 80MB of data, and it holds a record of the entire blockchain, more than 680,00 blocks and 342GB of data. Many cryptocurrency blogs and websites use the terms node and miner interchangeably, but a node is not a miner; but a miner could operate a node to support mining activities.

Miners cherry-pick transactions from the mempool; naturally, they are attracted to higher-paying transactions and prioritise those yet are limited to approximately 1MB of data in a block.

Once miners compose a block of desired transactions, they begin calculating the proof-of-work target, which is a computational puzzle. The puzzle’s difficulty exists to regulate the interval between when blocks are mined, which is approximately one every ten minutes. The difficulty adjusts every 2,016 blocks, which should equate to every 14 days if the desired one block per ten minutes target is maintained. If blocks are mined too fast or slow, the difficulty is increased or decreased to regulate the interval.

Although the size of each block is approximately a mere 1.3MB, the complexity arises from the puzzle, which essentially relies on a bit of luck and the number of times you can try your luck at solving the proof-of-work target. Miners with more processing power are capable of producing more attempts at solving the puzzle. The more computing power brought onto the network results in the difficulty being increased to regulate the one block per ten minutes target.

Firstly, you initiate a transaction from your wallet. A transaction must be authorised by a signature generated by a matching public and private key combination. Transactions with valid signatures are broadcast to a Bitcoin node.

A Bitcoin node does two things; it hosts a memory pool (mempool) of unconfirmed transactions, which is approximately 80MB of data, and it holds a record of the entire blockchain, more than 680,00 blocks and 342GB of data. Many cryptocurrency blogs and websites use the terms node and miner interchangeably, but a node is not a miner; but a miner could operate a node to support mining activities.

Miners cherry-pick transactions from the mempool; naturally, they are attracted to higher-paying transactions and prioritise those yet are limited to approximately 1MB of data in a block.

Once miners compose a block of desired transactions, they begin calculating the proof-of-work target, which is a computational puzzle. The puzzle’s difficulty exists to regulate the interval between when blocks are mined, which is approximately one every ten minutes. The difficulty adjusts every 2,016 blocks, which should equate to every 14 days if the desired one block per ten minutes target is maintained. If blocks are mined too fast or slow, the difficulty is increased or decreased to regulate the interval.

Although the size of each block is approximately a mere 1.3MB, the complexity arises from the puzzle, which essentially relies on a bit of luck and the number of times you can try your luck at solving the proof-of-work target. Miners with more processing power are capable of producing more attempts at solving the puzzle. The more computing power brought onto the network results in the difficulty being increased to regulate the one block per ten minutes target.

The puzzle Bitcoin miners solve

A block of Bitcoin transactions is put through a hashing function to create a 64 character long or 256-bit hexadecimal number. The resulting hexadecimal number should be below a certain target; if it’s above that target, the miner must adjust the contents to change the hash outcome. Miners collectively repeat this process over 180 million trillion times (>180 quintillions) per second.

Miners use a parameter in their blocks known as a nonce. A nonce is a single number that is increased in each attempt to alter the resulting hash without changing the block contents. It’s not just a race to see who can do this process faster as not all miners are working with the same block contents, meaning each miner is starting from a different place, hence why we can compare this process to a lottery.

In some cases, miners might need to adjust the block configuration by adding or removing transactions if simply adjusting the nonce value isn’t enough.

Miners use a parameter in their blocks known as a nonce. A nonce is a single number that is increased in each attempt to alter the resulting hash without changing the block contents. It’s not just a race to see who can do this process faster as not all miners are working with the same block contents, meaning each miner is starting from a different place, hence why we can compare this process to a lottery.

In some cases, miners might need to adjust the block configuration by adding or removing transactions if simply adjusting the nonce value isn’t enough.

Bitcoin difficulty target

Bitcoin miners are trying to guess a 256-bit number below a certain value, the difficulty setting defines that value. Per the lowest complexity setting, miners are guessing a number between 0 and 2,695,994,666,715,063,979,466,701,508,701,963,067,363,714,442,2540,572,481,103,610,249,215 (about 2^224) and if the number is larger, then they need to keep guessing. In this case, any numbers between 2,695,994,666,715,063,979,466,701,508,701,963,067,363,714,442,2540,572,481,103,610,249,215 (approx. 2^224) and 11,579,208,923,731,619,542,357,098,500,868,790,785,329,984,665,640,564,039,457,584,007,913,129,639,936 (2^256-1) would not be valid.

As the difficulty increases, the range decreases, meaning the possibilities are fewer. To standardise the length of the hashes, they are represented as a hexadecimal number preceded by zeros to ensure a length of 64 characters.

From the table below, you can see hashes from previous blocks. As time goes by, the numbers get smaller, highlighting a smaller range of successful guesses.

As the difficulty increases, the range decreases, meaning the possibilities are fewer. To standardise the length of the hashes, they are represented as a hexadecimal number preceded by zeros to ensure a length of 64 characters.

From the table below, you can see hashes from previous blocks. As time goes by, the numbers get smaller, highlighting a smaller range of successful guesses.

Block |

Date |

String |

Hash (decimal) |

Length |

09.01.2009 |

00000000839a8e6886ab5951d76f411475428afc90947ee320161bbf18eb6048 |

13859490975360805551058475875921983160016493905856282248190309916744 |

68 |

|

18.08.2010 |

00000000000ace2adaabf1baf9dc0ec54434db11e9fd63c1819d8d77df40afda |

4445059630506688046733136889679028568868828735750187027976466394 |

64 |

|

03.08.2013 |

000000000000003887df1f29024b06fc2200b55f8af8f35453d7be294df2d214 |

354849258364936913169335792211723370023059979681430592737812 |

60 |

|

18.12.2017 |

00000000000000000024fb37364cbf81fd49cc2d51c09c75c35433c3a1945d04 |

3542105908743678568170700468267143228978687811763068164 |

55 |

|

02.05.2021 |

00000000000000000005b0199ccf91c9d24e7ca515713db54abb665c9958f784 |

544791707064619165068591244863212355376078050203072388 |

54 |

Here is an example of us hashing moneyhub.co.nz and using nonces to reach a target that begins with just one zero, let alone 8, which is the easiest Bitcoin hash target.

Domain |

Hash |

moneyhub.co.nz |

6524cbceddff0e1756ad8dcb91e932b135e218ecf810659d6be29285effb8bd9 |

moneyhub.co.nz 1 |

6b746317db14b383e150620815af4495f309e69bf2486d7581377bb41a7c682d |

moneyhub.co.nz 2 |

6059ca19a2240c1879e6ec70eb9a6c7693b19193938accb279461043d0a44ef9 |

moneyhub.co.nz 3 |

047c553d154be5cc11e5d0dfc19de8c83f19aa7ccf37b443b78fecbc8de5e35e |

Is it possible to start mining Bitcoin?

Yes. But the better question is whether it’s profitable or not. There is no denying that large mining operations make money, but can the average New Zealander make money mining Bitcoin? The answer is probably not, at least not without joining a mining pool and purchasing special mining equipment. Even with a high-performance gaming laptop, it’s unlikely you’ll be able to cover the cost of your electricity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Bitcoin mining profitable?

Considering that Bitcoin miners earned an average of NZ$80.2 million per day in April 2021, mining is definitely profitable for some. However, the barrier to entry is very high, which is why new miners join mining pools and combine their resources with other miners. When a mining pool completes a block, the reward and network fees are distributed proportionately.

If Bitcoin transaction fees are voluntary, why are they so high?

Miners can choose which transactions to include the blocks they process, so they prioritise the transactions that will pay the most. Bitcoin users set network fees to ensure their transactions will get picked up sooner rather than later; the lower the fee, the longer you’ll have to wait.

Why does Bitcoin mining need so much power?

You may have heard anecdotes of early Bitcoins mined on laptops in 2010. You may also have seen news clips of enormous Bitcoin mining farms sucking up power from local communities. It’s hard to understand how the ecosystem went from laptops to warehouses full of high-power computers when the size of a block is less than one or two megabytes, lower than a medium-quality photograph.

The reason is because of the artificially adjusted network difficulty. The more resources that join the network, the faster blocks can be mined, so the difficulty is increased. According to the network difficulty as of the 1st of May, approximately 150 million terahashes per second were performed by the bitcoin network, and a terahash is one trillion hashes, meaning 150 Quintillion attempts to guess the target each second.

The reason is because of the artificially adjusted network difficulty. The more resources that join the network, the faster blocks can be mined, so the difficulty is increased. According to the network difficulty as of the 1st of May, approximately 150 million terahashes per second were performed by the bitcoin network, and a terahash is one trillion hashes, meaning 150 Quintillion attempts to guess the target each second.

Can I mine Bitcoin on my laptop?

A high-end gaming laptop could generate around 20 million hashes per second and use approximately 100 kWh. Using the CryptoCompare mining calculation tool, we can see that mining under these circumstances would not be profitable. Assuming electricity costs NZ$0.172 per kWh, we’d end up with a loss of almost NZ$150 per year under these circumstances.