Spending Your Savings in Retirement - The Definitive New Zealand Guide

Understand how to spend your retirement savings with our comprehensive guide covering common myths, decumulation risks, the Safe Withdrawal Rate, taxation on investment returns and many other must-know considerations. No retiree is the same; our guide aims to address individual circumstances for a secure and satisfying retirement.

Updated 15 July 2024

Summary:

Know This First: This guide has a lot of useful information and is, arguably, a slow read published to help you understand the wider issues many people encounter when deciding how to spend their investments. We've collaborated with industry experts who have generously dedicated their time to empower everyday New Zealanders to make optimal financial decisions. If you have any suggestions for improvement, please contact our research team.

Our guide covers the following:

- Our research team is continously asked the same question by many retirees - "how do I invest my nest egg to provide for my retirement?"

- Everyone invests different, based on their attitude towards risk, their capacity for loss, their anticipated expenditure profile and the major unknown for most, how long the nest egg will need to last, i.e., when will you die.

- Our guide covers myths and misinformation about retirement spending, the risks of decumulation (converting investments into spending money, e.g. the opposite of accumulation) and must-know facts about the challenges every retiree-to-be faces when planning spending in retirement.

Know This First: This guide has a lot of useful information and is, arguably, a slow read published to help you understand the wider issues many people encounter when deciding how to spend their investments. We've collaborated with industry experts who have generously dedicated their time to empower everyday New Zealanders to make optimal financial decisions. If you have any suggestions for improvement, please contact our research team.

Our guide covers the following:

- Myths and Misinformation about Retirement Spending

- What Risks Does Decumulation Face?

- Understanding that Our Traits Can Have a Disastrous Impact

- Financial Awareness, Cognitive Impairment and Vulnerability

- Increasing State Retirement Age (and a Later Entitlement to State Super)

- Spending Patterns, Inappropriate Assumptions and Financial Planning Tools

Myths and Misinformation about Retirement Spending

Much has been printed about the Four Percent Rule. Unfortunately, some may still believe this is the golden 'fits all' rule, but the reality it's not. By way of background:

No Retiree Spends Like Another

- Back in 1994, an American, Bill Bengen, a graduate from MIT in Aeronautics and Astronautics who subsequently became a financial adviser, carried out some research on how much an individual could withdrawal safely each year from their retirement nest egg.

- The research allowed for the annual withdrawal to increase by an assumed rate of long-term inflation and would last for 30 years (a typical retiree's life expectancy at the time plus a margin for error).

- His published findings were based on a simple investment portfolio, half in government debt and half in large US company shares; his research was based on actual investment returns from this investment over the preceding 75 years.

- This research led to the concept of a Safe Withdrawal Rate (SWR).

- But the flaws in the research were around the fact that it didn't allow for charges (adviser fees, fund management costs); in addition, it didn't allow for taxation on investment returns or the income paid out.

- As an example, savers in New Zealand pay tax on taxable investment returns using their Prescribed Investor Rate (PIR), income tax rate, or at the companies' rate (unit trusts, some superannuation schemes).

- The research also assumed an investor invested in passive investments (funds that track movements in an index, such as the NZX10, S&P500 etc.) rather than actively managed funds (stock picking).

- Bengen subsequently published articles to allow for the impact of US taxation, and some assumed associated charges and updated his data which impacted his original work and, as one might expect, lowered the figures from the original 4%.

- However, the limitation is that few New Zealanders invest 50% of their savings into large US stocks and 50% into US Bonds exclusively in passive funds.

- As a result, it's essential to be conscious that in many instances, the SWR would have been higher than 4%, what Bengen was searching for a safe level, but his research was based on at least $1 left at the end of his assumed retirement lifetime.

- Bengen isn't alone in researching this issue; Morningstar (a global research and investment manager) publishes regular updates covering specific economies. This is relevant because countries have different taxation influences, their interest rate backdrop, and various companies to invest in.

No Retiree Spends Like Another

- The main issue with the Four Percent Rule is that the research merely showed what could reasonably be taken each year as income; however, no two retirees' spending patterns are the same.

- For example, one retiree might like to travel extensively for the first ten years of retirement, whilst another might want to indulge in a passion for classic cars. One couple might want to leave a set amount to their children on death, whilst another might have no children or no desire to leave money on their death, preferring to distribute during their lifetime and see the enjoyment it might bring to their family.

- In summary, we all have a unique idea of what retirement means and hence the profile of our spending.

- As such, couples need to have a heart-to-heart as early in their working life to see what retirement means to each. For example, one might want to work well past 65 and gradually retire when they hit, say 70, whilst another partner might want to ditch their job at the very first opportunity.

- If you have no idea about (average) spending patterns for retirees, look at the research produced by Massey University each year. But remember, these are average spends taken from several respondents to the Statistics New Zealand Household Economic Survey from their budgets.

- If the thought of looking through lots of bank statements and trying to remember where money was spent over the last year to form the basis of one's retirement spending, several online tools will break down your expenditure for you; our guide to the best budgeting apps available in New Zealand (some of which sync with your bank account) make getting a complete understanding of your finances a lot easier.

- Everyone's circumstances, desires, and goals are unique. So a blanket amount/percentage that can be sustained from one's wealth each year or stated in an academic paper is nothing more than an estimate and arguably risks being inaccurate because our spending patterns and needs aren't the same years in year one until we pass.

- To help explain the situation further, we discuss two common retirement spending myths below:

Myth 1 - Spending for one person equates to half of a couple's spending

If you look at your retirement budget, how much of your total annual expenditure will be affected by the death of one person? The car still needs servicing and being insured, the home needs heating and maintenance, and at least one room will still need lighting each evening. White goods will still expire just as quickly. Where savings might be made are in food, clothing and personal expenses and, to some degree, travel costs, although the cost of accommodation might not be reduced by 50%.

The NZ government agrees, given the amount paid out in State Superannuation differs - you can see the latest weekly rates of superannuation here. However, it's important to note that the single person receives 65% of a married couple's entitlement.

The NZ government agrees, given the amount paid out in State Superannuation differs - you can see the latest weekly rates of superannuation here. However, it's important to note that the single person receives 65% of a married couple's entitlement.

Myth 2 - People are Living Longer

It is important when assessing how long the income is needed (retirement to death), one takes into account the fact that providing an income for a couple has a different dynamic to someone living alone, not least because life expectancy of the last to die for a couple is statistically older than one person living alone. Unfortunately, Stats NZ's life expectancy web-based tool is based on an individual rather than a couple.

A high-profile American financial adviser who has written extensively on retirement income has a very useful link to a calculator on his website.

By way of example, the Excel table suggests the life expectancy of a couple who are both aged 60 today, projecting forward to age 85 that:

But:

A high-profile American financial adviser who has written extensively on retirement income has a very useful link to a calculator on his website.

By way of example, the Excel table suggests the life expectancy of a couple who are both aged 60 today, projecting forward to age 85 that:

- There is an 18% probability that the male will be the sole survivor

- There is a 32% probability the female will be the sole survivor

But:

- There is a 66% probability one of the couple will be alive; we just don't know which one. When we do, we have a good handle on how long they are still likely to live. But also note that having reached the revised life expectancy, the individual's expectancy moves out further.

- So how does one stretch out retirement money if, having reached life expectancy, you are told you are likely to live X more years? You can't make money appear out of thin air. You must build in a sensible margin for error. Whilst lifestyle choices will impact life expectancy (heavy drinking, smoking, obesity and being a couch potato vs regular walks, healthy eating and low blood pressure etc.), another good pointer is, arguably, the experience of your forebears.

- Remember that your grandparents' life expectancy was considerably lower than someone who retires today. Still, longevity is hereditary, so your adviser should be asking for these details when advising you on a reasonable timeline for retirement to the grave.

What Risks Does Decumulation Face?

Decumulation refers to converting accumulated savings or assets into a regular income stream during retirement. It's the opposite of accumulation, which involves saving and investing money to build up a retirement nest egg during one's working life. For most New Zealanders, the decumulation phase typically starts when someone retires and begins to draw upon their savings, investments, or KiwiSaver.

During the decumulation phase, retirees may choose from various strategies to generate a steady income stream, such as:

Know This: Each decumulation strategy has its advantages and risks, and retirees need to consider their financial goals, risk tolerance, and individual circumstances when making decisions about their retirement income. As a result of the challenges, some New Zealanders consider consulting a financial advisor to help them navigate the various options and create a tailored plan for decumulation. However, this is not without its risks; we outline these below:

During the decumulation phase, retirees may choose from various strategies to generate a steady income stream, such as:

- Drawdowns: Withdrawing a fixed amount or a percentage from their savings or investments regularly (e.g., monthly or annually).

- Dividend income: Investing in dividend-paying shares or funds to receive a portion of the company's earnings as income.

- Home equity release: Using home equity release schemes, such as reverse mortgages, to access the equity in their property to generate income.

Know This: Each decumulation strategy has its advantages and risks, and retirees need to consider their financial goals, risk tolerance, and individual circumstances when making decisions about their retirement income. As a result of the challenges, some New Zealanders consider consulting a financial advisor to help them navigate the various options and create a tailored plan for decumulation. However, this is not without its risks; we outline these below:

Risk 1 - Bad advice

This could come in several guises, but examples might be:

- Working with a financial adviser who is out of their depth, perhaps because they use the same process for decumulators (retirees who are spending their savings) as accumulators.

- Working with a financial adviser who tells you what the adviser thinks you want to hear to secure the sale (for example, "Yes, Mr. & Mrs. client, this fund will keep on generating X% per annum returns, so you can withdraw $Y from your pension pot and never run out of cash").

- The adviser doesn't ask all the necessary questions to advise you properly.

- The adviser charges excessively for their services through commissions (initial and each year) or fees. We like the idea of a fee-for-service that isn't linked to the value of the investment being advised on, and have listed advisors who offer this in our directory. In the decumulation phase, it makes the remuneration of an adviser difficult because, for most of us, we aim to spend every last cent (perhaps leaving the value of the house for our heirs) so that when we die, there is maybe just a dollar left in our account. But that means the adviser who takes a commission from your fund each year will receive less and less remuneration. There could come a time when their interest in your affairs isn't so high, especially if they can secure more remuneration from another client. Fees taken from your retirement pot impact what is safe to take from the fund to pay for the retirement you want.

- The adviser who fails to get to grips with your attitude towards investment risk (how much you are willing to tolerate in short-term swings in the value of your fund). But if they have undertaken proper research, they then fail to advise on whether, given your financial provision for retirement, and your retirement budget, you need to take on as much investment risk. Generally:

- Most attempts to gauge one's attitude to risk are carried out via a short questionnaire of as few as six questions. This can be re-evaluated each year, but the concern is that one's attitude towards investment risk doesn't fundamentally change; our capacity for loss does change.

- Regularly re-evaluating one's attitude towards investment risk can lead to confusion brought about by our own behavioural biases, which are influenced by our most recent experiences; if the news carries stories of large stock market gains and everyone around us is making money from their investments will, inevitably lead to us being willing to take on risk, but when the news is full of share market declines our willingness to take on investment risk diminishes.

- What might be better is to look at our psychology of money. Companies such as Schroders in the UK have spent time developing robust online questionnaires to get to grips with our attitude towards money and investing.

- For many years, advisers worldwide have also used software provided by Finametrica to get to grips with their client's attitudes towards investment risk.

Risk 2 - Your adviser fails to get to grips with your capacity for loss

In this scenario, we are referring to your adviser getting to grips with what your ideal retirement looks like and, if investment returns took a tumble or inflation stayed higher than their assumption for a prolonged period, what cuts you would be willing to make to your agreed budget and for how long.

Also, advisers can use the wrong assumptions for future investment returns. Investment returns aren't a straight line; funds management groups might publish them as an average return over 3,5,10 and since inception, but these averages can mask big differences in the year-to-year performance, and this swing in actual investment returns can have a significant impact on the success or failure of your retirement plan.

Also, advisers can use the wrong assumptions for future investment returns. Investment returns aren't a straight line; funds management groups might publish them as an average return over 3,5,10 and since inception, but these averages can mask big differences in the year-to-year performance, and this swing in actual investment returns can have a significant impact on the success or failure of your retirement plan.

Risk 3 - The markets move against you

Market movements are one of the biggest risks to a successful retirement plan. Investing money into capital markets doesn't come with any guarantees; much of what is published about investment returns uses average annualised returns over some time, for example 3, 5, 10 years and perhaps since the fund started. But this hides the volatility (ups and downs) experienced by investors between each year that makes up the 'headline' average figure published. What is important here is timing. Are you fortunate to start taking money out of your pension fund as investment returns continue to track higher, or are you unfortunate and start drawing a pension just as investment returns go into negative territory for some time?

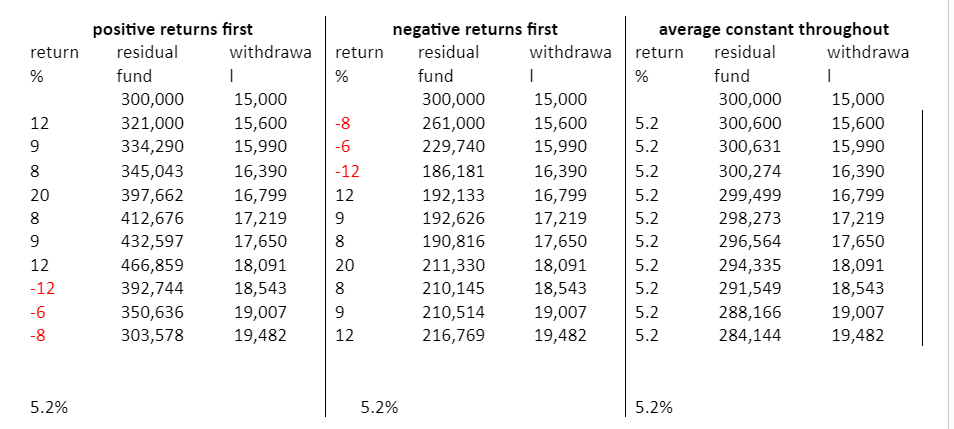

To help explain this, we publish a table below which presents three scenarios over ten years. In all three instances, the average annualised investment return is the same (5.20% after taxes and product charges). So we've assumed a 5% annual withdrawal in year one, increasing by an assumed level of inflation of 4% (inflation can be a bit sticky, note it was 7.2% for the year to the end of December 2022, according to Stats NZ.

To help explain this, we publish a table below which presents three scenarios over ten years. In all three instances, the average annualised investment return is the same (5.20% after taxes and product charges). So we've assumed a 5% annual withdrawal in year one, increasing by an assumed level of inflation of 4% (inflation can be a bit sticky, note it was 7.2% for the year to the end of December 2022, according to Stats NZ.

Our View:

- What is striking is the difference in outcomes. Under Scenario 1, the fund has pretty much kept up with the demands from the withdrawals taken (helped by positive investment returns during the first seven years); however, whilst the initial withdrawal in year one is 5% of the fund, the 10th year percentage withdrawal has risen to 6.4% of the current fund value.

- The initial 5% figure is unlikely to be long-term sustainable, but at 6.4%, it is less so. But that might not be an issue if an individual's life expectancy is limited or there is an expected change in spending habits, or maybe part of the plan is to spend the retirement fund and then dip into the equity in the home for the later years, when the impact of rolled up (deferred) and compounded interest is more palatable and fits in with your plans.

- However, Scenario 2 looks more dire; almost one-third of the fund has gone through the impact of negative investment returns for the first three years and inflation-adjusted withdrawals. The fund in scenario one is 40% larger than in scenario two, and the withdrawal in year 10 represents almost 9% of the starting year residual fund value. It is important to remember if the money is no longer invested (because you have taken the money as income), if investment returns improve the following year, it only benefits the money remaining in your pension pot, meaning it is harder, even with exemplary investment returns to repair the damage caused by the earlier years of poor investment returns. This is confirmed by the figures above; the damage has already been done despite seven years of positive returns after three negative years.

- All that might not matter if you have alternative ways of generating income on retirement (e.g. equity release from your home using a reverse mortgage), but what if you are relying on the fund for your retirement income? Ultimately you will be faced with the choice of a significant income reduction to protect the fund's residual value and its ability to provide you with income for your remaining lifetime (or identified period before another option comes into play).

- Alternatively, do you battle on knowing other plans and provisions will be called upon sooner than anticipated ('kicking the can down the road')? You might take the risk that you might just run out of money and resign yourself to living off of state superannuation earlier than planned. But all of this comes down to identifying your capacity for loss.

- Specialist financial advisers generally accept the first ten years of experience as a major determinant in the success or failure of one's retirement experience. Our tables above seek to rationalise that for you.

Understanding that Our Traits Can Have a Disastrous Impact

Behavioural finance means humans make irrational decisions, which can counteract the returns of positive markets or a solid investing strategy. We list some threats we pose to our successful outcomes:

1. Hyperbolic Discounting (myopic bias)

Hyperbolic discounting is the risk of choosing immediate rewards over later rewards; in the example above, the risk of taking too high (and unsustainable) income from the outset and living for today rather than the income value in the future.

2. Recency Bias

3. Anchoring Bias

Having been informed in the years leading up to retirement that a safe amount to withdrawal is $X, upon retirement, your adviser tells you that due to the worsening global investment outlook, the safe amount to withdraw is now $X-Y. But our trait as human beings is to anchor to what we have been told previously and based our expectations upon, and hence this bad news isn't accepted because we have anchored to a figure we were comfortable with.

4. Loss aversion

1. Hyperbolic Discounting (myopic bias)

Hyperbolic discounting is the risk of choosing immediate rewards over later rewards; in the example above, the risk of taking too high (and unsustainable) income from the outset and living for today rather than the income value in the future.

2. Recency Bias

- Is the risk that recent (investment returns) are taken to be a guarantee that they will continue into the future, leading to an unrealistic withdrawal strategy being put in place. For example, an investment fund that has achieved an annual average return of 10% over the past five years should not be taken that it will do the same over the next five years. Whilst it might be a reasoned recommendation to base a withdrawal strategy on that performance, it isn't reasonable.

- Starting a withdrawal strategy (based on past annualised returns over a relatively short period) might be a recipe for disaster. It would be wise to look at the backdrop as to why performance has been at that level. Governments have been trying to stimulate the global economy for some time, first to head off the Global Financial Crisis and, latterly, to offset the impact of Covid-19. We are now witnessing a reversal of that stimulus to try and slow the economy down via higher interest rates. But it has been a good time to be invested, whether it is shares or governmental/corporate debt (fixed interest).

3. Anchoring Bias

Having been informed in the years leading up to retirement that a safe amount to withdrawal is $X, upon retirement, your adviser tells you that due to the worsening global investment outlook, the safe amount to withdraw is now $X-Y. But our trait as human beings is to anchor to what we have been told previously and based our expectations upon, and hence this bad news isn't accepted because we have anchored to a figure we were comfortable with.

4. Loss aversion

- Loss aversion covers the fact that human beings feel the pain of losses far greater than the euphoria of gains. It can lead us to take irrational actions. If you have a financial adviser, they may have factored into their recommendation the fact that there could be a sharp and significant downturn in investment returns (and as we will cover in our next instalment, has documented it in a jointly signed retirement spending plan) but in the face of these losses you panic and redeem your investment (possibly at the bottom of the market, just as investment returns take a turn for the better).

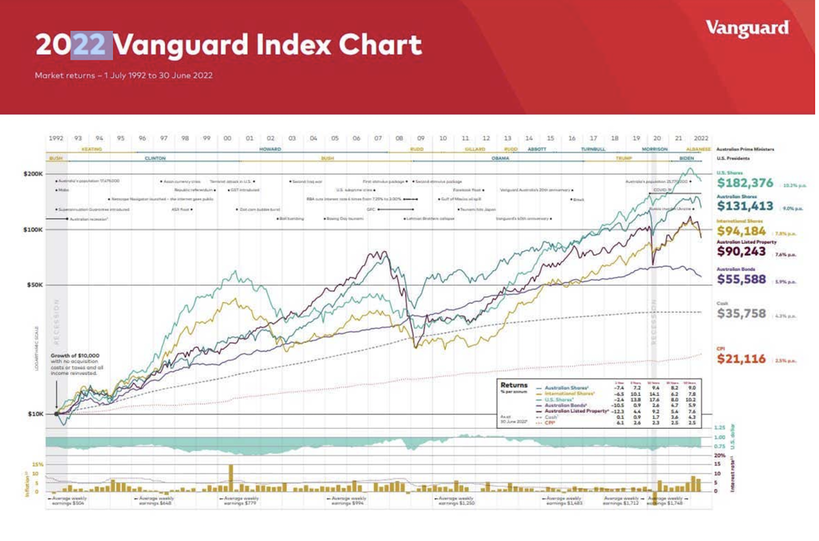

- The issue then is, having lost money on redeeming your investment (thereby crystallising the loss), you become too scared to put your money back into investments to generate your retirement income. Ups and downs in share markets have always been the norm and will continue to be so, as the chart from Vanguard below (a passive investor) illustrates so well.

- We have deliberately selected 30 years rather than a chart showing returns for 50 or 100 years because no one in retirement intends to invest for the following 50 or 100 years, whereas most of you will be hoping your retirement stretches that long

5. Regret

Having bought an investment and seen it fall in value, we buy more to lower the average price paid in the hope it will recover in value and cover up our regret in buying the investment in the first place. So it's important to take advice, particularly from someone independent and can offer an unbiased appraisal of your investments, someone without emotional attachment.

Having bought an investment and seen it fall in value, we buy more to lower the average price paid in the hope it will recover in value and cover up our regret in buying the investment in the first place. So it's important to take advice, particularly from someone independent and can offer an unbiased appraisal of your investments, someone without emotional attachment.

Financial Awareness and Cognitive Impairment

- Finance is full of acronyms and terms that have never been explained or asked about because we didn't want to appear ignorant. MoneyHub is designed to explain what’s important, but there is still a knowledge gap among everyday New Zealanders.

- We are exposed to marketing material showing us staggering headline investment returns (but with little explanation on how they were achieved, what risk was taken by the fund manager and whether that risk was adequately rewarded by investment gains secured) and, in many cases, our greed.

- However, before investing, it's essential to always understand what you're buying. If you're using a financial adviser, challenge them on their assumptions; why are they assuming what they assume? Where did they get their figures from to make those assumptions? Is that information reliable and reasoned (as opposed to reasonable)?

- Our cognitive ability decreases with age; according to the American Academy of Neurology, mild cognitive impairment affects 6.7% of people between the ages of 60 to 64, and rates climb steadily after that (just as most of us start our retirement journey and reliance upon our savings and the advice we receive on investing those savings) reaching almost 15% for those aged 75 to 79 and 25% for those aged 80-84. So, what might have made perfect sense to us on retirement day, will (inevitably) become harder to grasp and understand as we age.

- If you use a financial advisor, it's likely the adviser that they will themselves retire during your retirement journey, meaning you will need to rely upon the advice from their successor or the adviser working for the firm your original adviser sold their business to when they retired. So there must be someone there to help in the selection process or to challenge the advice from your adviser or their replacement.

- Every retirement plan not only needs to be documented, it needs to have longevity, and that means bringing in younger (trusted) family members from the outset because if we do this, we secure continuity for our retirement, we increase the chances that those we choose to take ownership of this responsibility, as we age, know the plan agreed from the outset, can ask the questions of an adviser when presented with a pivot in the advice acted upon previously to see if the revised advice has merit or is just plain bad.

- It's essential to consider executing an enduring power of attorney covering your finances to those entrusting your financial assets within the (hopefully) later years of your retirement. It is problematic if you don't execute an enduring power of attorney, likely to slow up decision-making and put at risk the success of the financial plan put in place.

Anticipating vulnerability is essential:

- As we age and lose mental capacity, we become more and more vulnerable, hence why we have covered the need for an enduring power of attorney and involving a (younger) trusted family member. But our vulnerability isn't just limited to our mental capacity; it also stretches to the fact that there is little room for error in planning our retirement and the investment outcomes we experience.

- For example, if you have agreed with your adviser that you can take $X from your retirement funds each year for the next Y years and the assumptions turn out to be wrong, or there is a significant and prolonged downturn in investment returns, there are consequences. Usually it means you have to cut, or even stop taking income from your retirement fund, that hasn't been quantified as part of an assessment of your capacity for loss, then you will be left living off of state superannuation for a potentially extended (and unplanned) period.

- Had you still been earning a salary, issues such as these can perhaps be covered by working extra hours or delaying retirement plans, but you are no longer working, possibly you don't want to have to return to work, maybe your health won't allow it, and of course with age comes the issue of trying to find work, in essence, you are vulnerable from a financial standpoint also.

Increasing State Retirement Age (and a Later Entitlement to State Super)

If you are a decade plus away from retirement, you might want to factor in the risk that a future NZ Government imposes an increase to the state retirement age. Some tinkering has already been implemented around entitlement to state superannuation for migrants. Governments worldwide have started to raise or are on a stated trajectory to increase the state retirement age. You may have seen the recent protests in France. The UK has already started its journey with some baby boomers now having to wait until 67; whilst the UK government has stepped back from bringing forward further increases, age 68 UK state retirement age is already provided for, affecting those who aren't 68 before 2037.

According to research from the OECD, state retirement ages are increasing in 20 of the 38 nations covered. Whilst not a vote winner, it is clear the global workforce is shrinking (there are shortages in the US and UK, with the UK Chancellor recently asking people to come out of retirement and start working again to ease pressures within the economy, even including measures in the recent budget to help). Still, the number of retirees is increasing, putting pressure on workers to fund state superannuation. As a footnote, any increase in entitlement to state retirement age will, unless current provisions are amended, result in the later entitlement to access KiwiSaver. So if you are committed to retiring at 65 or younger, you may need to put a plan of action in place to assist in funding for income before entitlement to Stare Superannuation and/or KiwiSaver kick in.

Whilst our comments around a change in direction around longevity might delay any change to NZ state superannuation entitlement, it is possibly only a matter of time before changes are announced. Your financial plan stress testing should make allowances for future change.

According to research from the OECD, state retirement ages are increasing in 20 of the 38 nations covered. Whilst not a vote winner, it is clear the global workforce is shrinking (there are shortages in the US and UK, with the UK Chancellor recently asking people to come out of retirement and start working again to ease pressures within the economy, even including measures in the recent budget to help). Still, the number of retirees is increasing, putting pressure on workers to fund state superannuation. As a footnote, any increase in entitlement to state retirement age will, unless current provisions are amended, result in the later entitlement to access KiwiSaver. So if you are committed to retiring at 65 or younger, you may need to put a plan of action in place to assist in funding for income before entitlement to Stare Superannuation and/or KiwiSaver kick in.

Whilst our comments around a change in direction around longevity might delay any change to NZ state superannuation entitlement, it is possibly only a matter of time before changes are announced. Your financial plan stress testing should make allowances for future change.

Spending Patterns, Inappropriate Assumptions and Financial Planning Tools

Many retirement plans are based upon the need for an increased annual income. But is that borne out by research? As we have said, it is vital to map out your retirement plans. As we have pointed out, it may well be the case that your retirement can be split into periods, perhaps ten years of being active, 15 years of being more sedentary and five years requiring increasing levels of support. This 3rd phase could be quite short, and whilst that might entail assistance with your care, research suggests that most people don't spend that long in residential care accommodation.

In an article by Marty Sharpe published in Stuff in October 2018, Government statistics suggested the median time spent in a government-funded accommodation was only 1.7 years. Of course, you may self-fund this from your retirement fund; however, the point here is that whilst care costs are high, they aren't generally incurred for a significant period.

If you're using a financial advisor, there are some questions to ask and considerations to make:

Know This: Some advisers might not use any planning tools and revert to Bengen's Four Percent Rule or worse, what the fund they are recommending you to invest in has done over the last 3,5 or even ten years; they might rely on 'tools' from the Sorted website. The problem with Sorted's decumulation tool is that it is based on a straight-line (average) investment return using expected returns from a balanced fund (which might not match your attitude to investment risk, there are other problems as outlined in our related guide).

Sorted's assumptions follow a similar path to Scenario 3 in our table that covered sequencing of investment returns, and as we have already highlighted investment returns are never a straight line, so you may be let in a false sense of security and wonder why your investments have dropped so far in value and how they can then possibly fund your retirement aspirations. The trouble is, by then, it's likely too late to repair the damage already done. Sorted's assumptions for its retirement income tool can be found at Sorted.org.nz

If you are reading this guide and are already retired, double-check the investment fund that has been selected. Is it the same as your spouse or different? If it is different, then the amount you can withdraw safely should be different unless there are dramatic differences in health, age, or spending one pot in preference to another. On the other hand, if you are both spending the separate pots at the same rate, something may well be wrong, and you must speak with your financial adviser as soon as possible if they can't provide you with a full and reasoned explanation, you may need to look elsewhere.

This might be better explained by looking at the performance of a popular fund management group offering KiwiSaver Funds. Below we provide excerpts from the fact sheets produced by Milford Asset Management focusing on their balanced and conservative funds and performance to 28th February 2023. We are not recommending that you invest with Milford, nor do we comment positively or negatively on their performance.

To explain things better, MoneyHub Founder Christopher Walsh walks through a Milford KiwiSaver Fund Update:

In an article by Marty Sharpe published in Stuff in October 2018, Government statistics suggested the median time spent in a government-funded accommodation was only 1.7 years. Of course, you may self-fund this from your retirement fund; however, the point here is that whilst care costs are high, they aren't generally incurred for a significant period.

If you're using a financial advisor, there are some questions to ask and considerations to make:

- How does your adviser set the income you can reasonably take each year to fund your retirement aspirations? You need to know this as part of future planning whilst you are working towards your retirement and then (and) importantly as you reach the final months before retirement and your adviser fights with your behavioural biases in determining if your retirement spending plans are reasonable or need rethinking, and then as part of keeping tabs on progress to make sure their assumptions are being borne out in reality and ensuring you are you keeping to your retirement budget.

- Some advisers may offer access to computer software based on a Monte Carlo simulator, which looks at historical investment returns from various asset classes. But be careful as to how long the research is based on. If it's too short, it will be hugely influenced by a massive global stimulus that has distorted investment returns for the past 15 years and won't include the impact of events such as the great depression, two world wars, the oil crisis, Black Tuesday etc. The adviser then makes their assumption about future inflation. The computer software then runs at least 1,000 simulations mixing up all the data from the past to ascertain a likely outcome (the result that the software generated most often). This is usually presented to the customer as a chance for a successful output.

- You need to agree on the chance of success you are willing to take. Remember that whilst an 80% chance of success seems highly likely, their plans will be destroyed for 20 people out of 100. Bear in mind the vulnerability of a retiree's situation. What is also important to keep at the forefront of your mind is that these reports are based on at least $1 left in the fund at the age you have agreed will cover your life expectancy. If you live only one year past that assumed date, you could potentially only have $1 plus state superannuation to live on. So it's important to get to grips with the output and ask questions about what the programme suggests your pot will be worth when you reach the assumed life expectancy.

- Other advisers might use a lifetime cashflow programme that also allows for what if you spend slightly more in years 1 to 5 and slightly less in 6 to 10 etc.) and stress testing architecture where the software allows the adviser to 'Stress test' outcomes by inserting actual historical investment returns in the past covering a period of extreme share market returns such as 'Black Tuesday' (1987), the Dot Com Crash 2001 and the Global Financial Crises 2008, the latter two events requiring over four years for the S&P500 index in the US to recover its losses for example. This stress testing helps quantify if the investments took a bad tumble, how robust your financial plan is, and what might need to happen (how much you need to reduce your income) to avoid running out of money. These programmes are reader-friendly, usually presented as bar charts showing the projected residual fund at the end of each year and income have taken during the year for all the scenarios you have discussed with your adviser. Some programmes allow the adviser to make the tweak in front of you as you plan out retirement.

Know This: Some advisers might not use any planning tools and revert to Bengen's Four Percent Rule or worse, what the fund they are recommending you to invest in has done over the last 3,5 or even ten years; they might rely on 'tools' from the Sorted website. The problem with Sorted's decumulation tool is that it is based on a straight-line (average) investment return using expected returns from a balanced fund (which might not match your attitude to investment risk, there are other problems as outlined in our related guide).

Sorted's assumptions follow a similar path to Scenario 3 in our table that covered sequencing of investment returns, and as we have already highlighted investment returns are never a straight line, so you may be let in a false sense of security and wonder why your investments have dropped so far in value and how they can then possibly fund your retirement aspirations. The trouble is, by then, it's likely too late to repair the damage already done. Sorted's assumptions for its retirement income tool can be found at Sorted.org.nz

If you are reading this guide and are already retired, double-check the investment fund that has been selected. Is it the same as your spouse or different? If it is different, then the amount you can withdraw safely should be different unless there are dramatic differences in health, age, or spending one pot in preference to another. On the other hand, if you are both spending the separate pots at the same rate, something may well be wrong, and you must speak with your financial adviser as soon as possible if they can't provide you with a full and reasoned explanation, you may need to look elsewhere.

This might be better explained by looking at the performance of a popular fund management group offering KiwiSaver Funds. Below we provide excerpts from the fact sheets produced by Milford Asset Management focusing on their balanced and conservative funds and performance to 28th February 2023. We are not recommending that you invest with Milford, nor do we comment positively or negatively on their performance.

To explain things better, MoneyHub Founder Christopher Walsh walks through a Milford KiwiSaver Fund Update:

- From the performance, you will note that the Balanced fund has consistently provided higher returns than the Conservative fund. Note our comments previously about annualised returns can be dangerous because it can hide dramatic falls and rises in values (the 'headline' numbers might be contaminated by one exceptionally good year and two reasonably bad ones) and the impact that might have from a sequence of investment returns perspective.

- It isn't always the case that a balanced fund will provide superior returns.

- Your adviser will be able to explain the backdrop to asset performance and how recent increases in global interest rates have impacted asset class performance (shares, government and corporate debt, cash etc.), the likes of which haven't been seen for a considerable period.