How to Take Income from Investments - The Definitive New Zealand Guide

Our guide explains strategies like Natural Yield, the Buckets Approach, Unit Encashment, and more to help you decide how to take income from investments during retirement. We also explain how to optimise your retirement income plan, prompts to re-review your strategy and must-know facts to consider.

Updated 16 May 2023

Summary

Know This First: This guide has a lot of useful information and is, arguably, a slow read published to help you understand the wider issues many people encounter when deciding how to take income from their investments. We've collaborated with industry experts who have generously dedicated their time to empower everyday New Zealanders to make optimal financial decisions. It should be read alongside our Spending Your Savings in Retirement guide. If you have any suggestions for improvement, please contact our research team.

This guide focuses on:

- Our guide explains various strategies, including Natural Yield, the Buckets Approach, Unit Encashment, and the Hierarchy of Spending.

- While the information may seem academic, it is published to help everyday New Zealanders understand the strategies available to tailor income to individual needs and adjust income throughout retirement.

- We extensively explain various strategies' basics, pros, cons and must-know facts to help you plan a retirement that puts you in financial control.

- Our focus is on explaining ways in which you can structure your retirement money to provide you with the income and capital expenditure plan you desire in the short-term while keeping your investments positioned for the long-term.

Know This First: This guide has a lot of useful information and is, arguably, a slow read published to help you understand the wider issues many people encounter when deciding how to take income from their investments. We've collaborated with industry experts who have generously dedicated their time to empower everyday New Zealanders to make optimal financial decisions. It should be read alongside our Spending Your Savings in Retirement guide. If you have any suggestions for improvement, please contact our research team.

This guide focuses on:

- Understanding and Applying Natural Yield

- Understanding and Applying the Buckets Approach

- Understanding and Applying Unit Encashment

- Understanding and Applying the Hierarchy of Spending

- Additional Strategies to Tailor Income to Your Income Needs

- Adjusting Income for the Retirement Journey

- Prompts to Review Your Spending During Retirement

Understanding and Applying Natural Yield (Also Known as Dividend Investing)

- Under this scenario, you choose one or a range of shares and live off the dividends generated each year; historically, dividends have generally kept pace with inflation over the long term; however, dangers are lurking for the unsuspecting.

- For example, something might happen beyond the control of the company you have invested in that necessitates them cutting the dividend, such as COVID, Government legislation, a costly and damaging court case, the list is endless.

- One way to reduce the risk of a cut in income might be to consider taking advice and buying a basket of shares of companies who have traditionally paid a high and growing dividend. Again, a share broker might be a good starting point; our guide to dividend investing explains more.

- For committed DIYers, plenty of index funds track the NZX50, US S&P500 and other sectors. Our guide to index funds has more details.

Drawbacks include (but aren't limited to):

- The receipt of dividends is unlikely to tie into your expenditure pattern, requiring some budgeting on the part of the investor (Dividends for the NZX product are paid in June and December each year)

- Investing in one company may not meet your attitude towards investment risk and your capacity for loss; it's highly risky and we're surprised with the lack of diversification amongst retirees. For example, too many in the past have been caught out by the failure of finance companies or a particular listed company.

- If you haven't kept back some capital to meet unforeseen capital calls or indeed known capital items (such as a major holiday or purchasing a car), you may have to sell down the investment; this might come at a bad time in terms of a last fall in the value of your investment, which will exacerbate the drop in future dividends paid to you, and so has a significant knock-on effect.

- One could lower the level of investment risk by buying some Government or Corporate debt, but this will pose a risk in terms of the ability of the dividends to keep pace with inflation, given the income from the bonds tends to be static. Furthermore, the yield from the bonds is subject to change; as one issue matures, the yield on the replacement investment could be lower.

More information: Our guide to dividend investing explains more.

Understanding and Applying the Buckets Approach

In this approach, you allocate your retirement savings to three (or more) buckets. For a three-bucket approach, they would be labelled short-term, medium-term and long-term income.

The short-term bucket (bucket one) will be filled with cash deposits and short-term government and corporate debt and is used to cover income and capital requirements for the first 3 to 5 years (depending on the view of your adviser, if you're using an adviser, as to what is short-term). You might also keep your emergency fund within this bucket, not to be spent but to be on hand should an emergency arise.

The medium term bucket (bucket two) will be filled with longer-dated debt, a small amount of large capitalised 'household name' shares and perhaps some large mainstream listed property investments. The idea here is for the income derived from these investments to cascade down into bucket one and to provide capital for expenditure when the money allocated to provide you with income when bucket one is exhausted.

Bucket three is the main driver of your retirement portfolio. It should be loaded with large, mid and small capitalised shares from around the globe; it will also have some listed property funds, perhaps some commodity funds (Gold and other precious metals). The concept here is that this bucket will provide a fillip to buckets one and two in the distant future. Allowing it to remain untouched for such a long period should negate the possibility of a poor investment return, given it is historically unusual for equity investments to post a flat or negative investment return over such a long timescale (we say negate, but it doesn't eradicate the risk, passive funds invested in many sharemarkets around the world failed to provide a positive return to investors for a series of periods after the technology bubble burst in the early millennia referred to by many financial commentators as the 'lost decade').

Warning: There is a caveat to this concept. It is important that, at least annually, you take stock of the investment returns from these buckets. If you feel there has been an excess return from any bucket, the money must be reallocated to another bucket or used to provide the agreed level of 'income' you require for a period of time. Returns from investments, particularly shares, revert to the mean. That is to say, there are periods where the return from shares moves higher than their 'moving average'. Eventually, they'll retreat (referred to as mean reversion), and the opportunity to truly take advantage of sharemarket investing is diluted.

Adopting this process also helps you to survive poor investment periods better; when there is a sharemarket crash, it can take an extended period for values to recover (the S&P500 took over four years to recover from the technology crash in 2001 and the Global Financial Crisis 2008).

The short-term bucket (bucket one) will be filled with cash deposits and short-term government and corporate debt and is used to cover income and capital requirements for the first 3 to 5 years (depending on the view of your adviser, if you're using an adviser, as to what is short-term). You might also keep your emergency fund within this bucket, not to be spent but to be on hand should an emergency arise.

The medium term bucket (bucket two) will be filled with longer-dated debt, a small amount of large capitalised 'household name' shares and perhaps some large mainstream listed property investments. The idea here is for the income derived from these investments to cascade down into bucket one and to provide capital for expenditure when the money allocated to provide you with income when bucket one is exhausted.

Bucket three is the main driver of your retirement portfolio. It should be loaded with large, mid and small capitalised shares from around the globe; it will also have some listed property funds, perhaps some commodity funds (Gold and other precious metals). The concept here is that this bucket will provide a fillip to buckets one and two in the distant future. Allowing it to remain untouched for such a long period should negate the possibility of a poor investment return, given it is historically unusual for equity investments to post a flat or negative investment return over such a long timescale (we say negate, but it doesn't eradicate the risk, passive funds invested in many sharemarkets around the world failed to provide a positive return to investors for a series of periods after the technology bubble burst in the early millennia referred to by many financial commentators as the 'lost decade').

Warning: There is a caveat to this concept. It is important that, at least annually, you take stock of the investment returns from these buckets. If you feel there has been an excess return from any bucket, the money must be reallocated to another bucket or used to provide the agreed level of 'income' you require for a period of time. Returns from investments, particularly shares, revert to the mean. That is to say, there are periods where the return from shares moves higher than their 'moving average'. Eventually, they'll retreat (referred to as mean reversion), and the opportunity to truly take advantage of sharemarket investing is diluted.

Adopting this process also helps you to survive poor investment periods better; when there is a sharemarket crash, it can take an extended period for values to recover (the S&P500 took over four years to recover from the technology crash in 2001 and the Global Financial Crisis 2008).

Understanding and Applying Unit Encashment from a Multi-Asset Fund (Conservative, Balanced, Growth funds etc.)

For many people with KiwiSaver and superannuation schemes, you may consider withdrawing an amount from a fund via encashment of units. This is simply asking the fund manager/KiwiSaver scheme to redeem a certain amount of money and pay it into your bank account. However, whilst this is a very simple approach, it also 'masks' some issues; not least, all these funds are a mixture of cash, government and corporate debt, listed property and shares.

The only difference is the percentage allocation to each asset class, with Conservative funds allocating more to the income-producing assets of cash and debt, whilst Growth funds allocate more to the growth assets of property and shares;. However, each unit comprises the same percentage to each asset class, so if a fund is made up of 40% government and corporate debt and 60% in shares, each unit sold reflects that same allocation, i.e. you cannot say to the fund manager "I want to encash some units but only those that relate to the shares".

As we have identified above, sharemarket investments should only be considered by those able to remain invested for 7 to 10 years or more (whether its 7 or 10 years depends on your view and that of your adviser - if you're using one - there's no firm line drawn in the sand as to whether it should be seven years or ten years. If you have a financial adviser and they are 'very' mature, he/she is possibly more likely to take the view of 10 years having probably worked through the events following Black Monday in the 80s, the collapse of Long Term Capital Management in the 90s along with the Asian crisis and more recently since the turn of the millennia the technology bubble, the Global Financial Crisis and the impact from Covid.

So, if you are encashing units from day one to pay you an income in retirement, you are technically selling down investments that really should be left untouched for much longer if you are to be shielded from sharemarket downturns which can be both quick and significant.

Furthermore, each fund is managed in accordance with its Statement of Investment Principles and Objectives (SIPO). You can ask your fund provider for a copy of the SIPO relevant to your investment. Within the document will be a statement relating to the investment manager's strategic and tactical asset allocation to each investment class (cash, debt, property and shares, for example); what this usually results in is the fund manager automatically rebalancing the fund (the regularity will be in the SIPO) which means the fund will continue selling down its best-performing asset classes to buy it's worse performing asset classes to remain within the strategic asset allocation bands it sets itself. Only during times when the manager invokes the Tactical Asset Allocation will that not necessarily eventuate.

The only difference is the percentage allocation to each asset class, with Conservative funds allocating more to the income-producing assets of cash and debt, whilst Growth funds allocate more to the growth assets of property and shares;. However, each unit comprises the same percentage to each asset class, so if a fund is made up of 40% government and corporate debt and 60% in shares, each unit sold reflects that same allocation, i.e. you cannot say to the fund manager "I want to encash some units but only those that relate to the shares".

As we have identified above, sharemarket investments should only be considered by those able to remain invested for 7 to 10 years or more (whether its 7 or 10 years depends on your view and that of your adviser - if you're using one - there's no firm line drawn in the sand as to whether it should be seven years or ten years. If you have a financial adviser and they are 'very' mature, he/she is possibly more likely to take the view of 10 years having probably worked through the events following Black Monday in the 80s, the collapse of Long Term Capital Management in the 90s along with the Asian crisis and more recently since the turn of the millennia the technology bubble, the Global Financial Crisis and the impact from Covid.

So, if you are encashing units from day one to pay you an income in retirement, you are technically selling down investments that really should be left untouched for much longer if you are to be shielded from sharemarket downturns which can be both quick and significant.

Furthermore, each fund is managed in accordance with its Statement of Investment Principles and Objectives (SIPO). You can ask your fund provider for a copy of the SIPO relevant to your investment. Within the document will be a statement relating to the investment manager's strategic and tactical asset allocation to each investment class (cash, debt, property and shares, for example); what this usually results in is the fund manager automatically rebalancing the fund (the regularity will be in the SIPO) which means the fund will continue selling down its best-performing asset classes to buy it's worse performing asset classes to remain within the strategic asset allocation bands it sets itself. Only during times when the manager invokes the Tactical Asset Allocation will that not necessarily eventuate.

- SIPOs can be found on every fund manager's website and from the Disclose Register administered by the Companies Office. MoneyHub Founder Christopher Walsh explains in the video below what a SIPO is and what it includes:

Further facts:

MoneyHub Founder Christopher Walsh explains in the video below what a PDS is, what it includes and what the information means:

- The other concern is during periods of extreme volatility; the fund can suspend redemptions or place illiquid 'tainted' investments in a separate fund' side pocketing', which allows for the untainted value to be realised, with further money paid to investors in the future, if or when it can redeem the illiquid investment held by the fund.

- This is contained in the product disclosure document (PDS) - you can download this from the fund manager's own website. It is important to understand what the PDS means.

- Hopefully, it will never come to the point of a delayed redemption or 'side pocketing', but you must have money set aside that is readily realisable to cover your income needs. If you're using a financial adviser and a multi-asset fund, you must cover this aspect with them before investing in your retirement fund.

MoneyHub Founder Christopher Walsh explains in the video below what a PDS is, what it includes and what the information means:

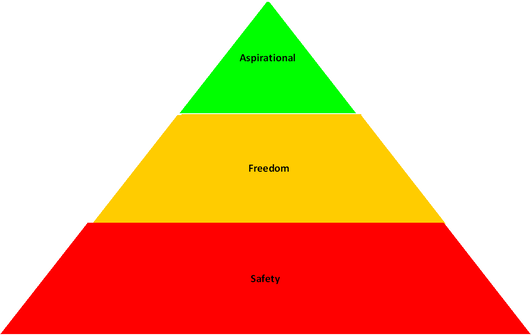

Understanding and Applying the Hierarchy of Spending

This is based on an amended triangle originally developed by Abraham Maslow, a US psychologist that sought to understand the motivations for human behaviour by mapping out different motivations within a pyramid structure. Financial Services professionals have adapted the triangle to represent retirement spending needs:

- Aspirational - covering gifts and bequests.

- Freedom money - money that will be used to enrich one's retirement and enable one to pursue dreams, be it travel/holiday, extra trips to the theatre, educational or wellbeing retreats; its expenditure on what you want to do in retirement.

- Safety money - the money needed to maintain yourself and your home but might also include expenditure on aspects of retirement you are unwilling to forgo. If you need at least one holiday per year for your wellbeing, then it's a non-negotiable item not to be covered by 'freedom money'. Of course, perhaps most of this identified expenditure could be met from state superannuation, but it is likely a top-up with be required from your own retirement funds.

Following the demise of Lifetime Asset Management's variable annuity product, New Zealand no longer has an annuity marketplace, there are no safe havens to provide a dependable and guaranteed income each year for life (especially given your life expectancy is a known unknown), exposing even our most essential (safety money) income need to the vagaries of investment returns on one's retirement fund. Our guide to retirement products offers alternatives, including the rebooted Lifetime scheme.

Know This: An annuity may still be an option for anyone who has retained a private or employer-sponsored pension scheme overseas. It will expose the income to the vagaries of exchange rate variations each year. However, this can be ameliorated to some degree by opting to use the services of a foreign exchange company, some of whom can offer a contract that guarantees an exchange rate for the following 12 months of expected income receipts, providing some short-term certainty and clarity.

Additional Strategies to Tailor Income to Your Income Needs

As outlined above, we covered ways of providing income from our savings, natural yield, buckets and unit encashment (this isn't an exhaustive list); we now look to identify some additional strategies to consider to enable you to adapt the income withdrawn to tighten the fit between the retirement fund and the income required from it. These strategies have been developed by US financial planners who specialise in the retiree marketplace.

1. Take a level of income from your pension fund

- This path allows for a considerably higher level of starting income from the retirement fund compared to an income that adjusts by inflation each year, enabling greater spending at perhaps a time when we can be more active.

- Studies in the UK suggest that a retiree's income needs to fall over their retirement journey in real terms (inflation-adjusted).

- With NZ State Super normally linked to the change in national average income, it may well be a retiree who takes the view that as most of their safety income need comes from the state superannuation so inflation proofing isn't so important, especially if they have mapped out their retirement journey.

- One word of warning, however, is that whilst inflation has been quite benign for over a decade, recent events may have triggered a rise in core inflation which might be with us for some time to come. Indeed the global economy may never get back to sub-2 % inflation, meaning a fixed level of income will lose its spending power much more quickly.

2. Guyton's Inflation Adjustment Withdrawal

- The "rules-based spending pattern" was developed by Jonathan Guyton, a US Financial Planner, and it is aimed at rewarding retirees when there have been excess investment returns, but also recognising periods when investment returns have been poor. Under this set of strategies, a retiree takes inflation-adjusted withdrawals each year apart from the year after a negative investment return has been experienced.

- Whilst this enables a higher initial withdrawal than an inflation-adjusted withdrawal programme without rules, research suggests that the income falls in real terms (inflation-adjusted) gradually over time.

- One might consider this route as a halfway house between a level income and an unfettered annual inflation-adjusted income; however, given research suggesting income needs do fall over time, it could be argued that this set of rules more closely meets the needs of a typical retiree allowing, as it does, a higher starting income when we are more active and in tandem declining gradually as our mobility declines.

- Further information can be found in a research paper authored by Dr Brancati et al entitled 'Understanding Retirement Journeys: Expectations vs Reality'. You can download this document here in PDF format.

3. Cap and Collar Adjustment

- Under Bengan's research, individuals adjust their income for inflation each year, but similarly, if deflation occurred, a retiree would also cut their income. This occurred in the early 1920s but would have been factored into Bengan's research on safe withdrawal rates we covered earlier.

- Given it is likely a retiree would have a low tolerance to cut income or indeed understand why they should, this rules-based approach sets a maximum and minimum adjustment to the level of income taken from one year to the next.

Know This: This strategy may well offer up a higher starting level of income than an inflation-adjusted income without rules. However, the amount of higher income would be determined by the level of the cap and the collar (and, if you're using a financial adviser, agreed with them); i.e. you agree to a 0% Collar (so even in deflation, the retiree doesn't take a pay cut) and, say, a 5% Cap to the maximum level of inflation adjustment to one's income each year. If inflation were to fall back below the 5% level, a retiree wouldn't notice any impact on their retirement income from inflation each year. If inflation remains stubbornly higher than 5% in the future, then a retiree's income will gradually fall in real terms. However, the payback is the higher level of starting income that can be taken.

Adjusting Income for the Retirement Journey

- All the above rules-based amends to Bengan's approach to a safe withdrawal rate have one common flaw (as outlined above).

- Whilst it might have relevance to our 'safe income' needs (which are non-negotiable must-haves year in and year out), it has little relevance to one's retirement ambitions for enjoyment: e.g. your "freedom money" and indeed aspirational income (gifts and bequests to people).

- Here is perhaps where your adviser adds the most to your retirement journey and may well necessitate you mapping out what will enrich your retirement and how long each phase of retirement might last

- Many financial advisers feel there are three phases to retirement a period when you are most active and receptive, which could be the first ten or maybe twenty years, depending on what age you decide to retire. There is then a period where you are less active, again that could last another ten years but means lower spending and finally there is the period where your are in "(your) god's waiting room". Where additional costs might be about paying for help around the home, assistive devices and a period where most discretionary expenditure ceases, but perhaps core expenditure rises. It is this part of one's retirement plan that can be impacted by applying the additional spending rules covered above. These spending rules are not an exhaustive list. We have just picked out a few.

Prompts to Review Your Spending During Retirement

Having addressed how much of your retirement wealth needs to be allocated to provide your safety expenditure, how to address the need for freedom money? Whilst you might have some ideas on what you want to do, are they the correct ones? Recent research from Morningstar suggests we aren't very good at planning out our ideal retirement because when asked about what our ideal retirement looks like, we blabber out the top of our mind priorities rather than what we really want to do and so prompts are more likely to elicit a more accurate reflection of our retirement plans. It's back to a big subject we covered under Behavioural Biases and, amongst others, recency bias.

Another prompt might well be around when you decide to work rather than have to. Some people live to work, whilst others work to live. If you are in the former camp, you will keep working until you drop (if you can), whilst, for the rest of us, we resign ourselves to working until state pension kicks in. But how many of us take a few seconds out to ask ourselves what is most important in our lives? When we are young and energetic, we have no money to enable us to facilitate our plans; when we are older, we have the money but perhaps not so much energy and the sad truth is that money cannot buy you time.

George Kinder, the pioneer of life planning and international thought leader, has devised three simple questions to help bring clarity to what is most important to us, their 'dream of freedom':

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

These questions elicit a raft of answers; quite common is time and how we spend it. For some, that might lead to a reassessment of how much longer we are willing to work, perhaps looking at our finances to see if we can supplement income from a mix of part-time work and savings until State Superannuation kicks in and brings some relief to retirement savings.

You may want to reassess what is important to you. Do you want to enjoy the here and now with those most dear to you or be one of the richer people in the graveyard?

Another prompt might well be around when you decide to work rather than have to. Some people live to work, whilst others work to live. If you are in the former camp, you will keep working until you drop (if you can), whilst, for the rest of us, we resign ourselves to working until state pension kicks in. But how many of us take a few seconds out to ask ourselves what is most important in our lives? When we are young and energetic, we have no money to enable us to facilitate our plans; when we are older, we have the money but perhaps not so much energy and the sad truth is that money cannot buy you time.

George Kinder, the pioneer of life planning and international thought leader, has devised three simple questions to help bring clarity to what is most important to us, their 'dream of freedom':

Question 1

- I want you to imagine you are financially secure (maybe you won big time on Lotto), that you have enough money to take care of your needs, now and in the future. The question is, how would you live your life?

- Would you change anything? Let yourself go. Don't hold back on the dreams.

- Describe a life that is complete that is richly yours.

Question 2

- This time you visit the doctor who tells you that you only have 5 to 10 years left to live. The good part is that you won't ever feel sick. The bad news is that you will have no notice of the moment of your death. What will you do in the time you have left?

- Will you change your life, and how will you do it?

Question 3

- This time the doctor shocks you with news that you only have one day left to live. Having read that sentence, notice what feelings arise as you confront your very real mortality (death happens to other people). Ask yourself:

- What did I miss?

- What did I not get to be?

- What did I not get to do?

These questions elicit a raft of answers; quite common is time and how we spend it. For some, that might lead to a reassessment of how much longer we are willing to work, perhaps looking at our finances to see if we can supplement income from a mix of part-time work and savings until State Superannuation kicks in and brings some relief to retirement savings.

You may want to reassess what is important to you. Do you want to enjoy the here and now with those most dear to you or be one of the richer people in the graveyard?

Our Conclusion - a Summary of Our Guide

Our guide covers many new ideas and it's not something easily digested. To help communicate the must-know points, we've summarised this guide and our guide to spending in retirement into 25+ points below:

If you use a financial adviser:

Further considerations

- The safe withdrawal rate bandied around from Bengan's research (which used a tax-advantaged savings scheme and invested 30% in US large companies, 20% in US Small companies, and 50% in US government debt looked at 30-year time horizons since the mid-1920s) is only a rough guess of what percentage of your retirement wealth can be spent each year. Indeed, the average of all 30-year periods resulted in a much higher sustainable withdrawal rate (around 7%), but it doesn't come anywhere near to securing bespoke quality financial advice that looks to match retirement capital against a proposed spending plan that may well vary over your retirement journey.

- We need to be mindful of ourselves and our behavioural biases, which are dangerous and can easily derail a competent financial plan.

- Due to the influence of sequencing of investment returns, the first ten years will almost certainly determine whether you are set for retirement or fulfilment or one of the compromises. Averaging morphs from being your friend in accumulation to your enemy when you come to spending down your retirement fund (dollar cost ravaging).

- Be clear on the hierarchy of spending. Maybe that results in you running two portfolios, one for safety income and one for freedom income.

- Make sure that if you seek advice, what you receive takes into account a reasoned allowance for longevity, remembering if there are two of you on this journey, it becomes even more complicated. Unless you have developed a medical issue, indulge in a dangerous pastime or abuse your body, it's likely you will have a similar life expectancy. It's best to build a margin for error in any planning you do.

- Take any fund performance stretching over more than one year with a pinch of salt. What is important is the individual years within the average, whether the manager took on investment risk in your name they were amply rewarded for (positive Alpha), whether they are a closet tracker fund and taking excessive charges, or whether their decision-making has been bad. Look also at the benchmark used to determine if the manager has performed well. Is it relevant or a smokescreen to suggest great performance when in essence, it's been quite mediocre.

- Be aware of your vulnerability both to bad financial advice and also to your decreasing cognitive ability. Involve a trusted (younger) family member from the outset. If you haven't already, execute an enduring power of attorney covering your finances. Your trusted relative might have to make decisions for you at some point.

If you use a financial adviser:

- Make sure they have a reasoned approach to retirement advice. If they use the same process for both decumulators (spenders) as accumulators, question the reasonableness of that. Our guide to financial advisers has more details.

- Question your adviser on the reasonableness of their assumptions. What is the basis for them? Furthermore, be wary of an adviser not offering either a lifetime cashflow forecast, stochastic model or some long-term research (like Bengan did) that covers multiple 30-year retirement periods over a reasoned period. Just looking at the past 30 years or less is fraught with danger. But the data needs to be representative of the recommendation. No point looking at Bengan's research but using a wholly domestic investment portfolio, the NZ marketplace isn't the same as the US.

- Realise that, when presented with a chance of success of, say, 80%, it means 20% of people will fail; that could be you. Do you like those odds? In addition, recognise that within the 80 people who were successful, it could well be the computer programme projects that in 30 years time they will only have a dollar in their account; If you live beyond the assumption that might be all you have left to take you through to your death.

- If the programme provides a dollar figure remaining in your retirement fund, ask if the amount is in real terms (i.e., it has the same spending power as it would today, or is it in nominal terms, meaning inflation will have ravaged its spending power and it might only represent a week's grocery bill).

- Be comfortable with the plan your adviser has drawn up for you. Remember, it doesn't really impact the adviser if they get it wrong, but it's a disaster for you. In addition, bear in mind the adviser sitting in front of you today is likely to have retired long before you get to the latter stages of your retirement, so the plan presented today may be reversed by their successor, who might have a different approach to advising retirees. Have a plan B.

- Undertake some reading on an appropriate strategy to decumulate. Ask why your adviser prefers natural yield, bucket approach, encashment of units or some other process. Be sure you are aware of the drawbacks of each and get a recommendation in writing from your adviser why their recommendation is better than other options based on your specific requirements.

- Quiz the use of the adviser's attitude to investment risk questionnaire and why it is better than other options. Make sure your adviser undertakes an analysis of your capacity for loss. Recognising that if there are two portfolios as outlined in 13 above, the influence from the capacity for the loss will be different; one you are relying on (safety), the other is freedom, you may still be able to take two holidays rather than 3 for a while that has less impact on your retirement, but there is no leeway in your safety income requirement because there aren't really many ways of reducing those cost; you could shop at Pak'N'Save rather than Countdown, you could switch utility provider, but the savings aren't going to be enough if your adviser gets it all wrong.

Further considerations

- For many, Bengan's safe withdrawal rate will be used for the safety income, meaning a different approach is required for any money left over for aspirational spending. Few of us will have a large enough fund where SAFEMAX will cover safety and freedom spending.

- Before giving up the rights to a UK pension fund for the 'red herring' tax advantages that might be suggested, consider whether a guaranteed income from an annuity that is only influenced by currency fluctuations is better or worse than drawing down from a fund which is subject to taxation, uncertainty over longevity and uncertainty over investment returns, which might be influenced by changes in currency fluctuations in any event. Current policies allow for a wide range of options to protect the amount invested should you die prematurely, including 30-year guarantee periods. An annuity no longer has to 'die' with you.

- Ask your adviser for a 'prompt' sheet that may well help you pinpoint what is important to you during retirement.

- Have that conversation with your partner to flesh out what retirement looks like and when it should start. Ask yourself George Kinder's three questions.

- Do some research on the subject, so you can engage with your adviser; there is plenty available from a Google search. A notable book on the subject is Beyond the 4% Rule by Abraham Okusanya.

- Be sure to meet with your adviser at least annually to update each other on progress and any changes to your agreed spending plans; this should include a review of the progress of your investment portfolio to make sure the current value sits within the parameters of your adviser's assumptions. If the portfolio is noticeably below where it should be, you may need to cull some spending to protect the value; if it's significantly higher in value, it might enable you to reduce the level of investment risk you are exposed to, have a one-off spend or undertake some aspirational spending.

- Ask your adviser if there have been any developments around options for providing income to retirees since you last met that might be relevant to your circumstances.

- Get to grips with your adviser's preferences for investing. Do they only recommend Passive funds, active funds or a mixture? Decide what fits with your own views of investing. See our previous coverage of Passive vs Active Investing.

- Be conscious and aware of the total amount of fees you are paying; research suggests that every 1% in costs results in a 0.5% reduction in the percentage it's safe to take in income from your retirement fund.

- Finally, get your adviser to provide a personalised (to you) one-page document that you both sign, referred to as a 'Withdrawal Policy Statement'. This will go a long way to avoiding future conflicts over what you think was agreed upon and what our adviser thinks was agreed or promised. It should include the following:

- What the baseline withdrawal strategy is

- The rate(s) of withdrawal from the retirement portfolio(s) (which might be varied if you're planning for a multi-step journey active, less active, sedentary

- Asset Allocation and portfolio management strategy

- How much, if any, will be held in cash as a buffer (to protect against prolonged share and the bond market falls as well as to cater for unforeseen expenses)?

- If appropriate, the order in which asset classes will be sold down to provide you with income

- How one-off lump sums (above the normal income requirements) will be provided

- A method of determining the amount that might be withdrawn, including trigger points for a reset (upwards and downwards)

- What your minimum acceptable income expectations are, split where appropriate between safety, freedom and aspirational, and in the case of Freedom and Aspirational, how long are you willing to tolerate a reduction or cut to that income (should investment markets take a severe tumble)?

- What will trigger a rebalancing exercise within your retirement portfolio?

- Is the value of your home part of the retirement income provision, and how (trade down, reverse mortgage), when is this envisaged?

- Frequency of review meetings with your adviser.